Report Card Writing Strategies for First-Timers

Feeling

clueless about writing report cards? You're not alone. Few colleges offer

courses in them and most school systems don't make time to offer formal

direction to new teachers. "If it weren't for teachers around me who

helped me figure it out, I would have felt as if I were almost making it

up," recalls Kim Wilkes, a teacher in Winter Park, Florida, about her

first report-card writing experience many years ago.

"It's

a time-consuming and stressful task," says Elizabeth Rae Merrill, a

teacher in Dobbs Ferry, New York. "To do it well, you must do a serious

evaluation of the students' work as well as their in-class performances, and

then synthesize all your observations into information that's useful to parents

and students."

Here

are some strategies and techniques to help you get started:

- Get

the Support You Need. "New

teachers not only need help preparing report cards, but from day one they

need to know what to collect for a report card," says Eileen

Thornburgh, a teacher in Boise, Idaho.

A first step is finding out if there is a paid mentor in school to help you. If one isn't available, seek out a teacher you trust. "We teachers talk all the time, at lunch, or in the teachers' lounge," says Thornburgh. "Use these opportunities to find out what you need to know."

- Gain

Clarity from Your Principal and "Model" Report Cards. Sit down with your principal and talk about the

school's grading philosophy. Check out models of report cards written by

other teachers in a similar grade or content area.

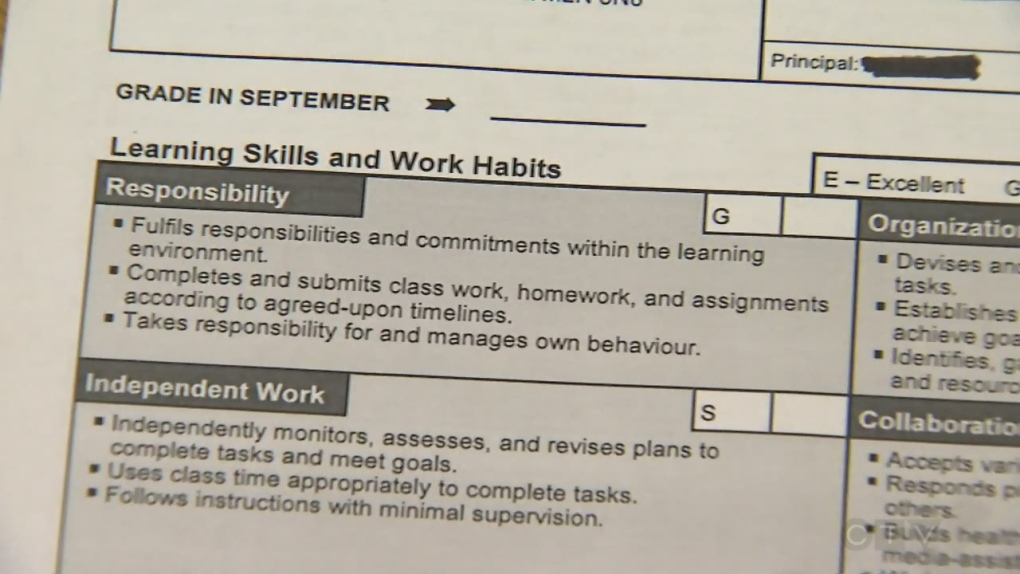

For most teachers, the purpose of a report card is to provide a snapshot of a student's academic, social-emotional, and work skills. "When I'm writing a report card, I'm writing a page of history. I want to represent this individual in all that they've done," says Paula Bautista, a teacher in New York's Westchester County. "It's for the parent, for the school, and for the next teacher who might need it."

When it comes to grading, the picture isn't so clear. Teachers tend to get scant input from the school about how tough or easy to be. As a result, grading standards often vary widely. "All grades are not equal. An A in one class may not be an A in another teacher's class," says Merrill.

Merrill believes new teachers have to know precisely what they're assessing. "Are you grading a student's progress in comparison to his previous work, or are you grading work as compared to his classmates? Are you grading effort or ability?" A grading policy that is clear, consistent, and communicated to parents at the beginning of the school year will help parents get a true picture of their child's progress.

- Get

Organized. If you haven't done so

already, check the school's academic calendar for report card due dates.

Then decide what tools you will use to make your evaluations, such as portfolios, checklists, inventories,

student self-assessments, anecdotal observations, and test results.

Setting up an assessment system is critical because finding time to reflect in a busy classroom isn't always easy. Says Bautista, "Kids need you; parents need you. We're just so incredibly rushed . . . and overloaded with curriculum. As a result, we assess on the spot, constantly."

To help identify a student's progress, Bautista narrows her focus. "Instead of trying to assess all of a student's work, I pull one sample a week that is truly revealing about a child. Some of the samples are going to be their best work, highlights. Other samples are their day in, day out stuff. For every big concept you're teaching, you want to have a sample to look at."

Bautista maintains a filing system that includes three separate folders for writing, math, and reading, all of which students may access. A fourth file is for her eyes only and might contain sensitive remarks or notes to parents. Bautista also uses a notebook to collect her daily observations, one for each content area. Students are listed with enough space next to their names for comments, such as this one she made about a student: "Wrote a really thorough science observation; was able to explain to me the volume of the rock she was testing."

At report-card time, Bautista sits on her bed or couch and spreads out a student's work and her notes around her. "I work like a painter. I step back and look. It's like my palette. I look, and it all comes together. I get a picture of that child." Then she begins writing.

- Choose

Your Words Carefully. For

many teachers, the most important part of report cards is writing

the narrative comments. "A child

isn't a B or a C+; a letter grade doesn't tell us where a child is or how

he has progressed. It's too tidy," Thornburgh says.

Some report card formats leave ample room for written comments. Others offer almost no room at all. "Basically, I have to sum up a human being in a box that is an inch-and-a-half deep and three inches wide," Thornburgh says. "It's important to write judiciously and sparingly."

Most teachers start with one or two positive sentences regarding the child's strengths and growth, academically and socially. A third sentence typically targets areas to work on, and a fourth thanks parents for their support and/or involvement, if appropriate. For example: "Tina has made impressive growth this term as a reader. Her sight-word vocabulary has expanded dramatically. We are working on using context to figure out unknown words. Thanks for exposing her to literature at home."

If a student is having difficulties or struggling with a concept, teachers need to be honest and tell parents in a professional manner. Select words that soften the blow and offer parents useful strategies for improvement so they can help address the problem. Always include at least one positive comment about the student and end the report card on an upbeat note.

"It's especially difficult to write a negative comment," says Jennifer O'Neil, a teacher in Philadelphia. "I'm always very careful how I say things. I spend hours choosing the right words so that the criticism is purposeful and constructive. I have two or three people read what I've written to make sure it's OK. My goal is to address the issue and have solutions or strategies for ways to improve the situation. I want parents to feel that we're all working together for a common goal, which is supporting that child."

- Be

Proactive. Experienced teachers are

emphatic about not waiting for report-card time to deliver any bad news.

"Most parents appreciate the fact that they do know the situation,

good, bad, or ugly," says Mary Rosenberg, a teacher in Fresno,

California. "That way they are prepared when they see the report

card."

Communicating well with parents before and after the report card is very important. Parent-teacher conferences can help greatly. Rosenberg sends home progress reports every three weeks, and finds parents appreciate this line of parent-teacher communication.

When a classroom crisis arises, Wilkes calls the parents right away. "Let's say you had a cheating incident; you gave the student an F, and he goes ballistic. Before the child gets home, I'll call the parent at work and say, 'Johnny left class very upset today. Here's what happened.'" Wilkes says, "You're taking the initiative instead of waiting to be on the defensive."

Being proactive also means documenting a child's behavior and academics and letting the principal in on the problem. That way the principal can be prepared or can offer support if a parent calls to complain.

You never know when a parent will respond negatively to a grade or a comment. It's best to be prepared for such situations before they happen. Rosenberg once had a child's father become furious when she told him his son was failing first grade, while the child's mother started crying. "When I called the vice principal to come in to the meeting, I was able to pull out all my copies of my progress reports, deficiency notices, phone notes, and home visits, and show the facts," Rosenberg says. "It wasn't about my having a bad day or not liking their child. It was about the whole quarter, right there. They apologized [for their outburst], and agreed to work with their son. We didn't have any more problems the rest of the year."

There's no doubt report-card time can be an emotionally intense experience for parents and teachers. "Have a Kleenex handy, especially when you discuss a report card at parent-teacher conferences," Bautista says. "And no matter what, always remember you're writing about someone's child — someone a parent loves."

This

article originally appeared in Teacher magazine, published by

Scholastic.

No comments:

Post a Comment